This UCLA professor teaches students about the science of dumplings and pie

Class has just begun on a recent Thursday at UCLA, and professor Amy Rowat and her students are watching as chef Vinh Nguyen sets up a table with a portable gas stove, a pot filled with water, a bowl of flour and a stack of chopsticks.

For the next hour, Nguyen demonstrates how to make wontons and scallion pancakes, discussing issues of temperature and texture, gluten and fat, while Rowat and her students ask questions. Nguyen rolls out dough, talks about lamination and hands out little bowls of just-cooked wontons.

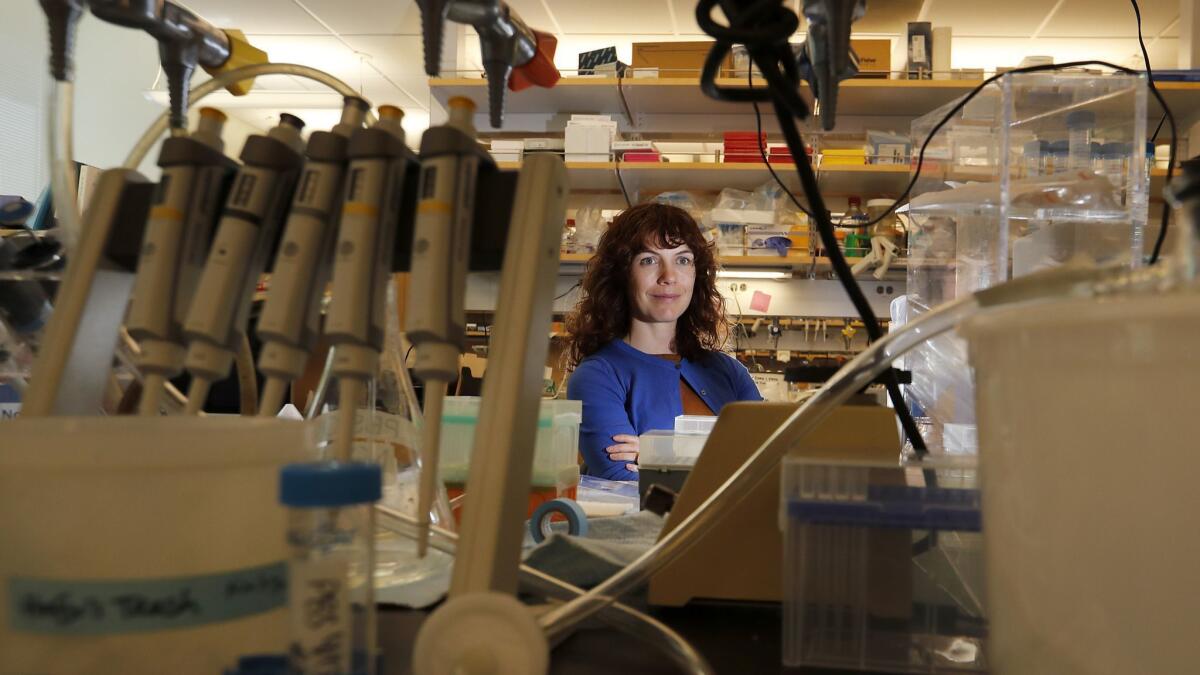

This is not a cooking school demo, but the Science & Food class that Rowat, 43, a professor of integrative biology and physiology, has taught for the last eight years.

If you think that baking pies and making dumplings isn’t science, well, you’ve probably never baked a pie or cooked a dumpling — or read Harold McGee’s landmark book “On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen.”

“We cover similar topics in my upper-level undergraduate cell biophysics class as I do in the Science & Food class,” says Rowat, smiling.

Every week, she brings in a guest to talk to her class — past visitors include baker Zoe Nathan of Huckleberry, farmer Barbara Spencer of Windrose Farms and Animal chefs Jon Shook and Vinny Dotolo — about topics such as emulsification and terroir. In-class experiments have included baking pies in toaster ovens. And every year there’s a “scientific bake-off,” where the students present their independent projects.

“Some students had never made a pie,” says Rowat later in her crammed office. “And then by the end of the class they’re baking pies. One student was delighted because he could bake pies for the frat parties.”

Rowat’s path to her Westwood classroom began in Guelph, the small town near Toronto where she grew up. And yes, she liked to bake. She went to school at Mount Allison, a small Canadian university, and then got her PhD at the University of Southern Denmark, where her PhD supervisor collaborated with the Nordic Food Lab, the project set up on a Copenhagen boat by Noma chef René Redzepi. She did a post-doc (on emulsions) at Harvard, where she set up a series of science and food lectures (Ferran Adrià and José Andrés were among the lecturers) that were the precursors to the talks that accompany her UCLA class.

At the lab a few hours after the dumpling class, the students regroup to discuss emulsions, doing experiments with cups, syringes, oil, water, food coloring and lecithin (an emulsifier found in egg yolks, soy beans, chocolate and, yes, Nutella).

“We started off doing just apple pies, but then we expanded in subsequent years to challenge the students to bake any kind of pie. So then there was the emergence of the cream pie,” says Rowat, sounding as if she’s considering a historical timeline. “There are lots of great scientific concepts in a coconut cream pie, for example.”

For instance, her students have used pie-baking to focus on how various fats affect crust flakiness, viscosity of fillings, the aeration of whipped cream and phase transition, which is why materials melt at certain temperatures.

This year she’s having her students shift away from pies to more general baking.

“Many of them live in dorms where they don’t have a lot of space, so we thought maybe cookies would be good.”

Another popular theme has been the effect of alcohol on the crust. “Schnapps or Goldschläger or rum or bourbon. That’s been a common project.” (Yes, this is a college course, but Rowat’s masters thesis was on the effects of alcohol on lipid membranes.)

“Recipes for baking are like equations,” says Rowat, which neatly sums up the idea behind her class — to use the structures of ordinary life to teach sometimes advanced scientific concepts.

Learning to bake with Huckleberry’s Zoe Nathan »

Rowat’s students, says Zoe Nathan, “are learning how to cook and bake in a way that is empowering, because they’re learning the whys and hows instead of just a recipe.” Nathan judged one of the annual scientific bake-offs, with fellow baker Christina Tosi of Milk Bar.

A few months ago, Rowat’s lab started research on generating cultured meat. “It’s animal-based right now, but we have ideas as to how it can be plant-based in the future.”

There have been efforts to develop a high school curriculum based on the Science & Food classes, and the class has also spawned a student group that meets separately to dissect the science of common foods. “They’ve done sessions on energy bars and kombucha, and then they make their own,” Rowat says.

On May 7, as part of the annual Science & Food public event series and The Times’ monthlong Food Bowl festival, Rowat will host the Future of Food in Extreme Environments at UCLA’s California NanoSystems Institute. The talk will address the issue of feeding people in outer space and in food deserts.

“Food is such a great accessible tool to teach science,” she says.

Instagram: @AScattergood

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.